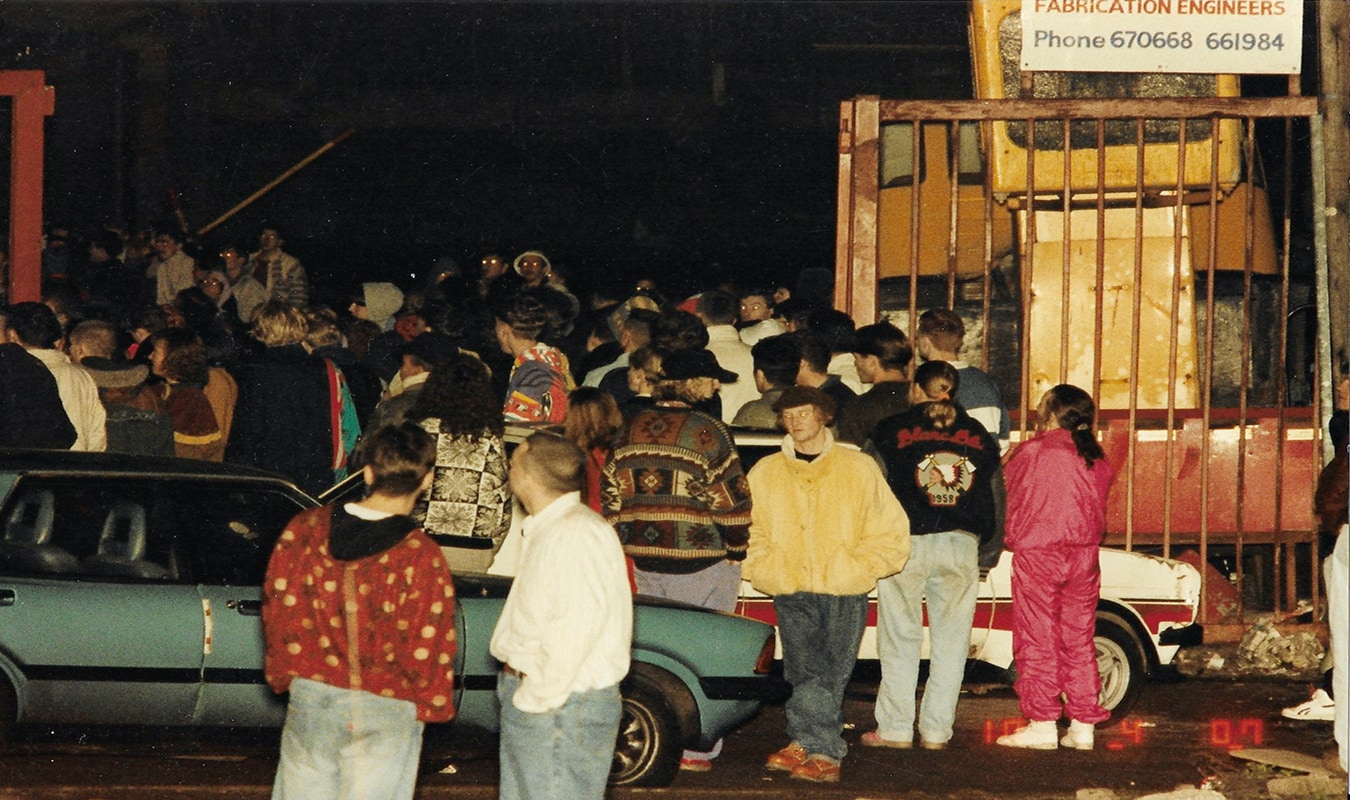

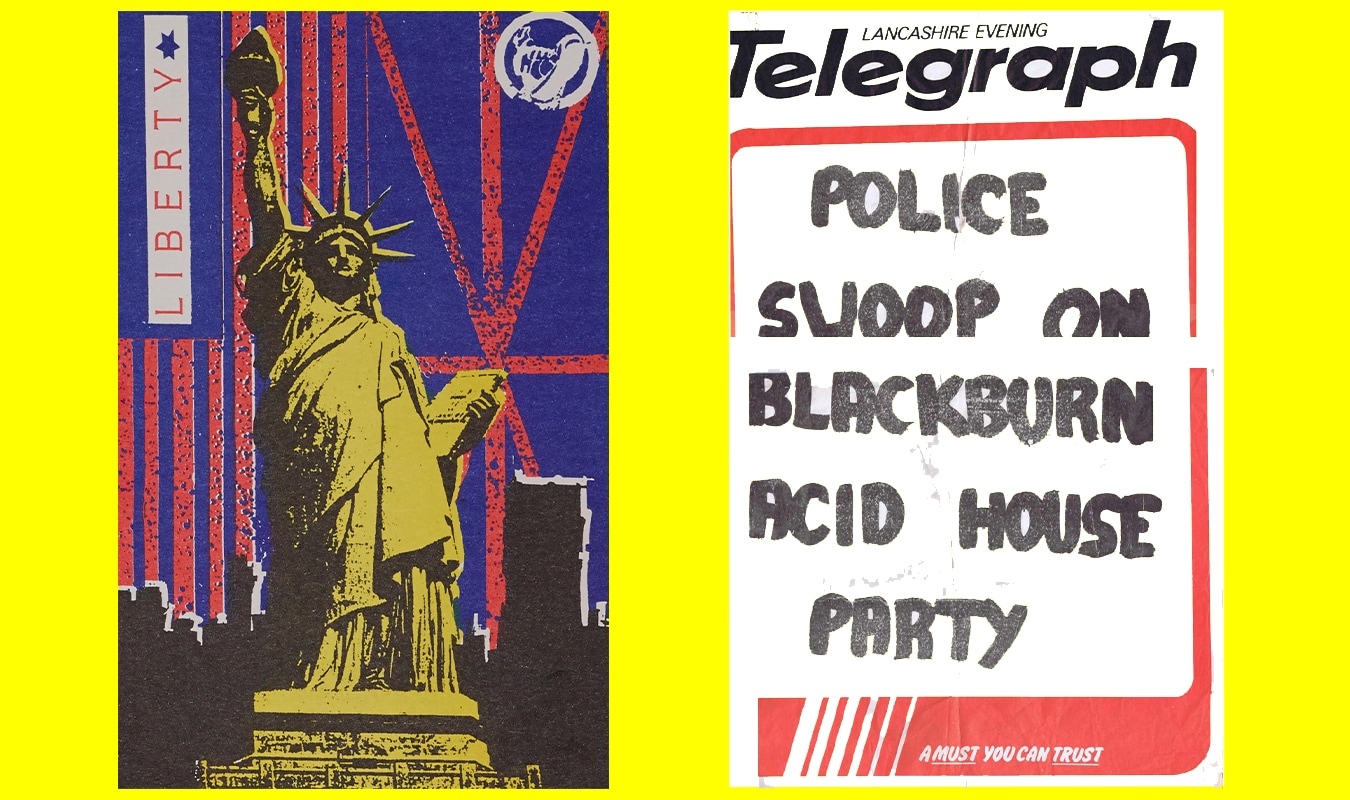

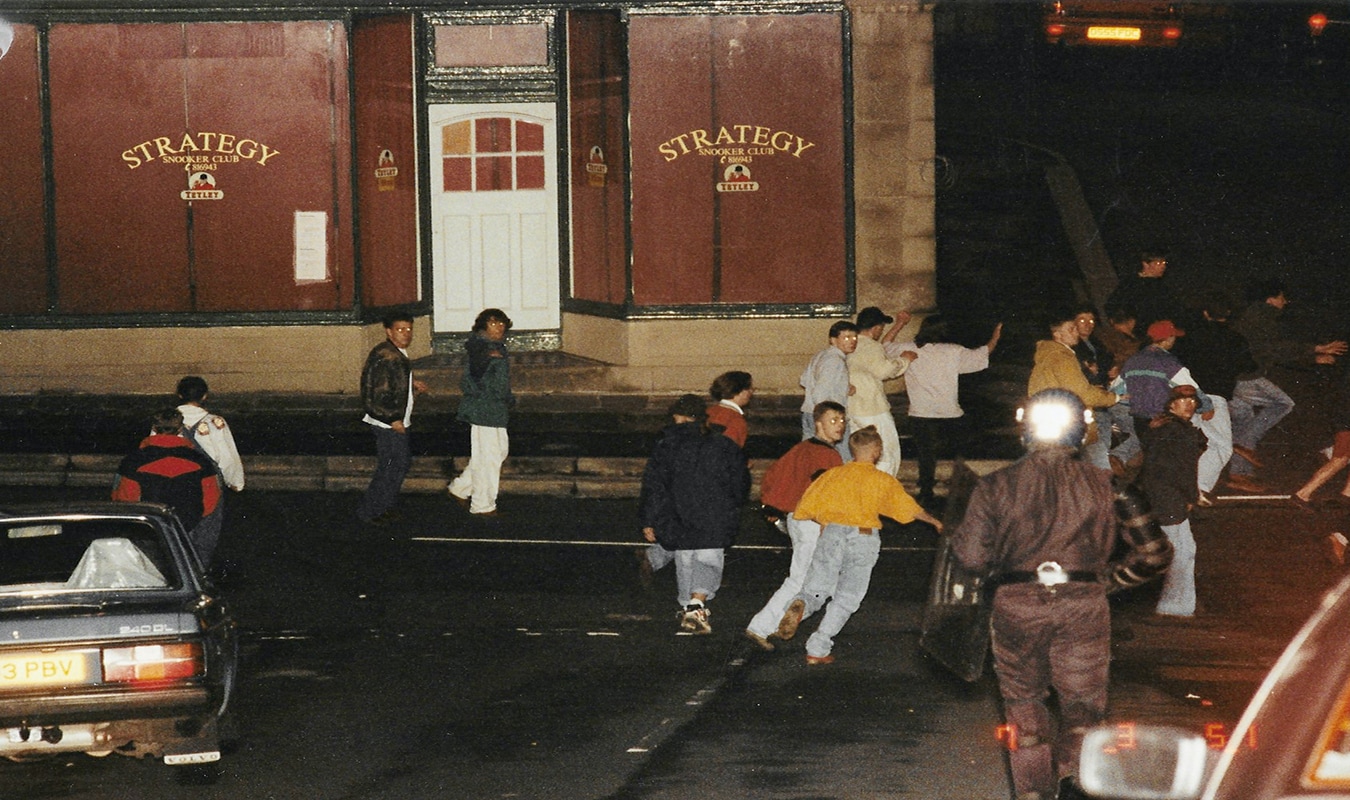

The end of the 1980’s was a time for rebellion, a chance for escapism from the regime and a period of determination for the young people of Blackburn. The empty warehouses and mills of the region were reclaimed by those young people to stage the greatest parties of their lives.

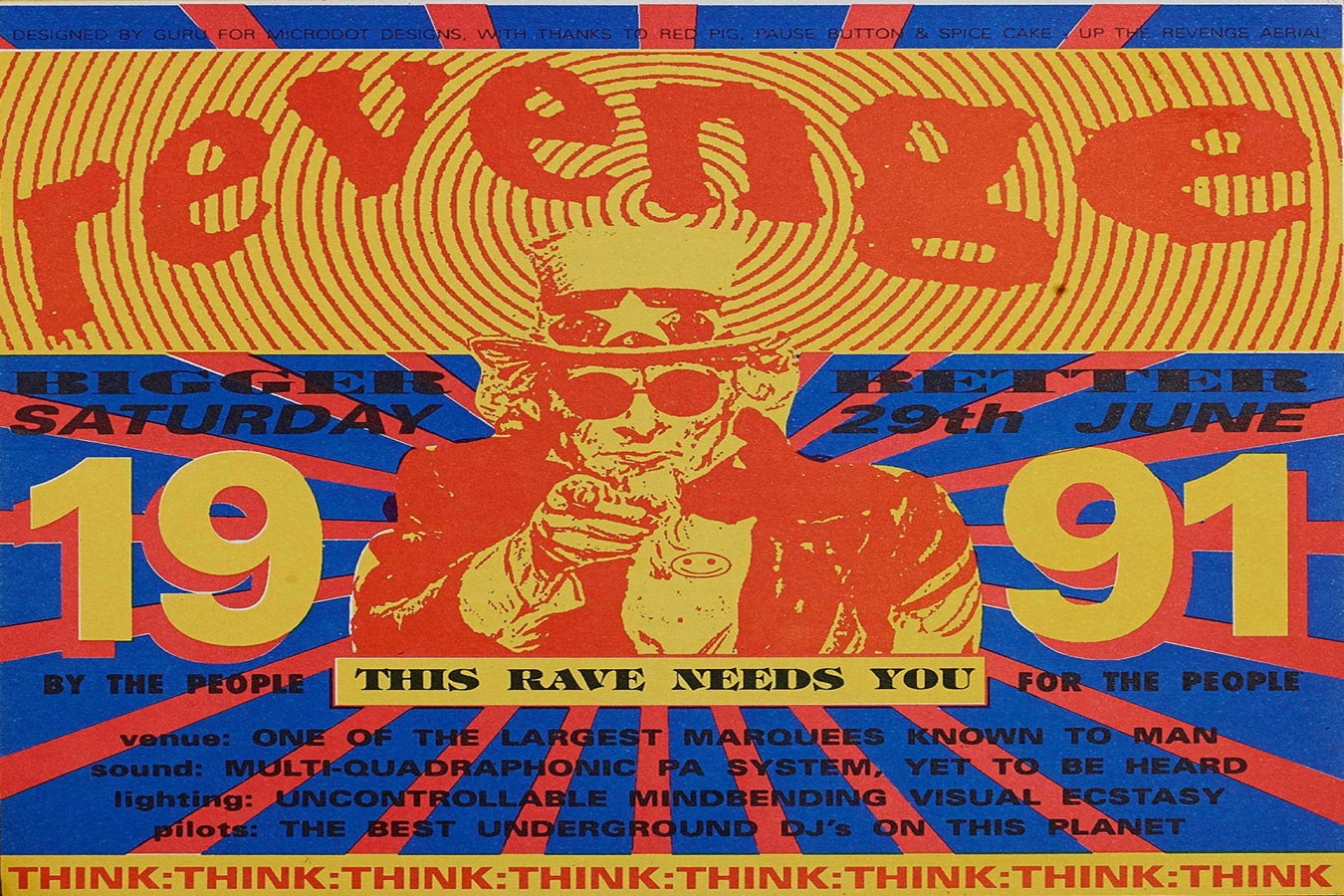

A generation of discarded, disenfranchised youths became the final piece of the puzzle in forming an underground movement that is regarded as one of Blackburn's greatest working-class revolutions, or otherwise known as Acid House, raves or 'Parties for the people - by the people'.

In turn, the online archive entitled 'Flashback' documents this snapshot in time. SEVENSTORE sat down with the curators of Flashback, Alex Zawadzki and Jamie Holman to divulge in their inner workings, aims and why this time in history matters.

SEVENSTORE: What is Flashback? What’s the story behind it?

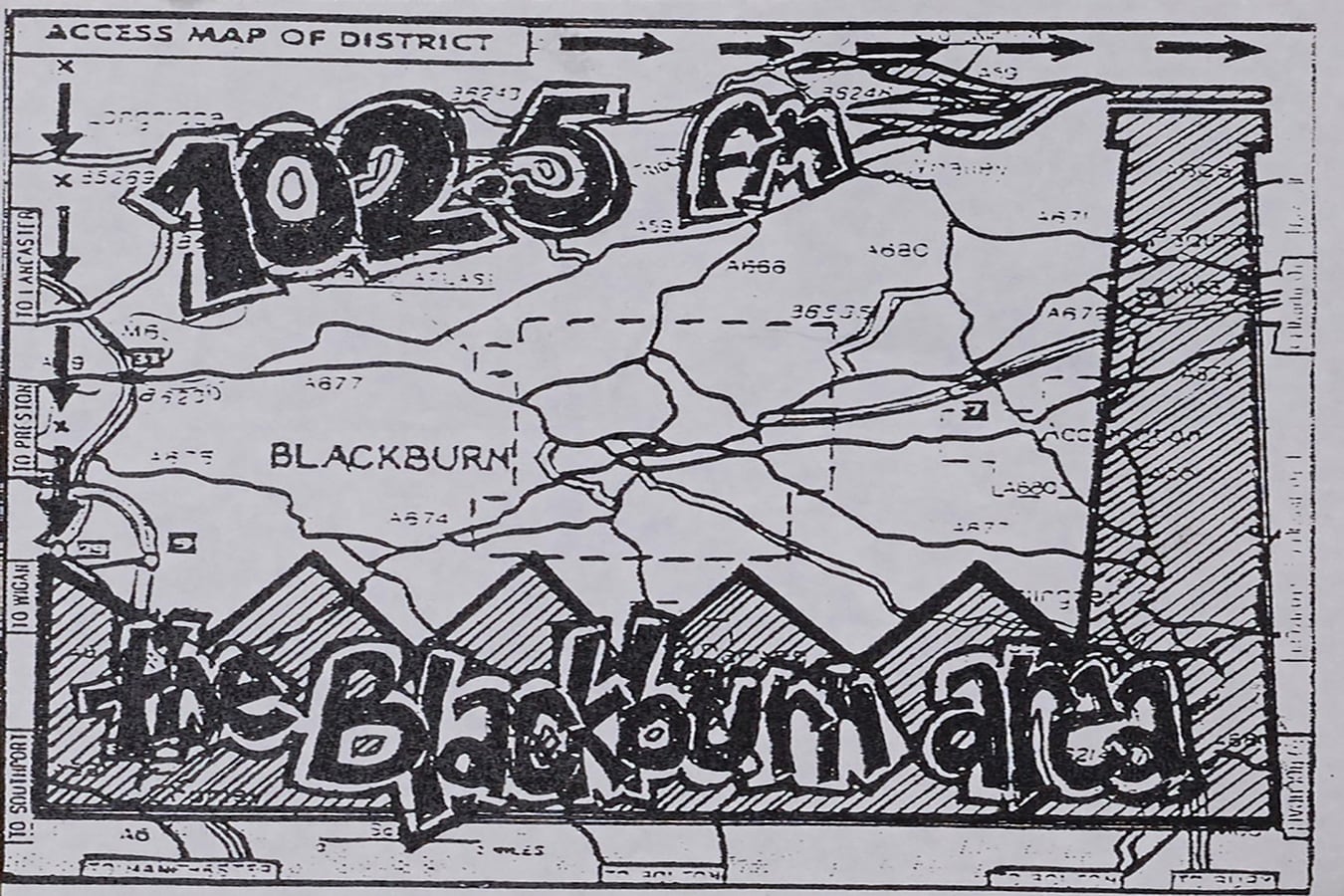

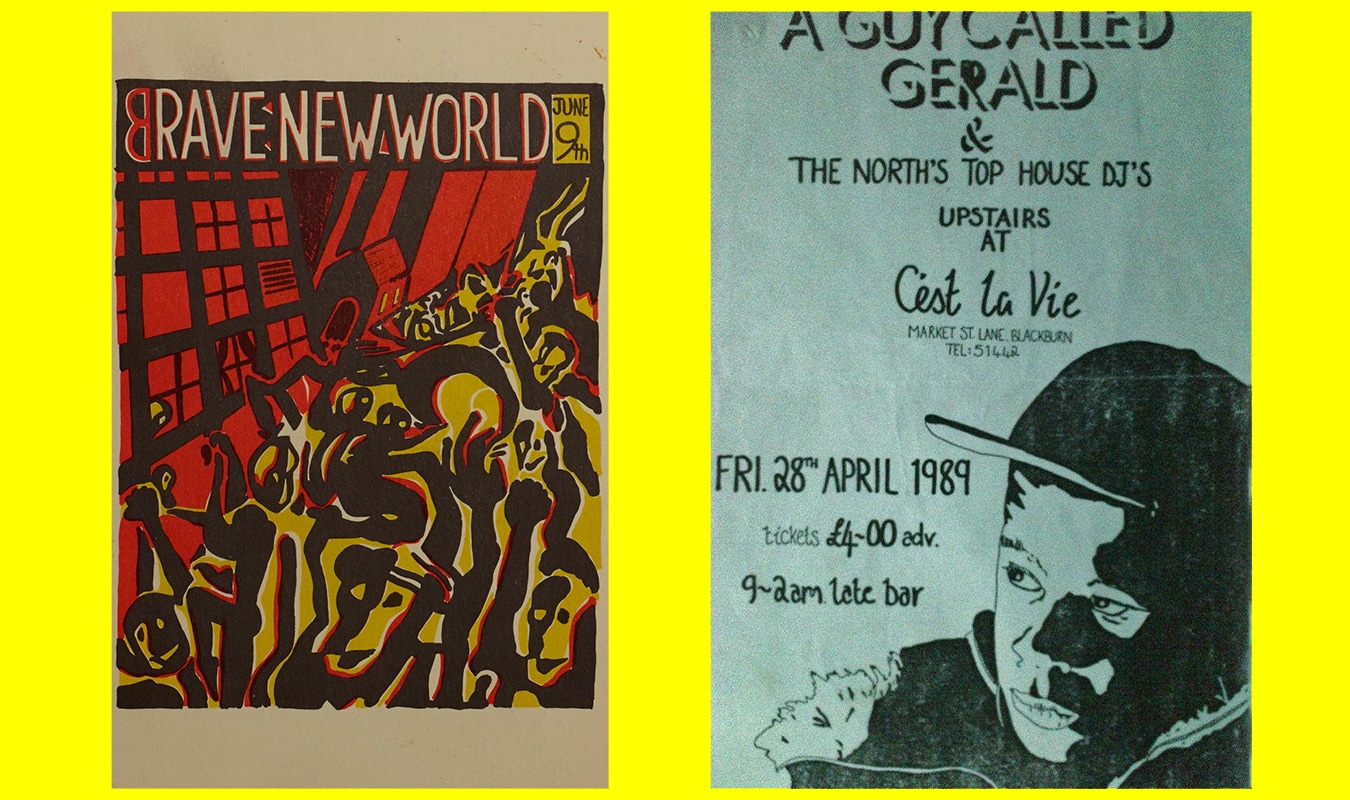

Alex: Flashback is a new archive for a modern age, it’s a collection of human stories behind Blackburn’s Acid House era known in Blackburn as ‘’The Parties’’ or across the UK as raves. We spent 8 months recording interviews with people involved in the scene from the organisers to the police; collating flyers, images and other materials that tell this uniquely working-class story.

We’re working up a new set of materials now which included never seen before photographs, interviews with residents, more female voices and the era's local MP Jack Straw.

You’ll find all this and more on the Flashback website - created with web developers Lighten and designer Made by Mason who worked with us to create transcripts and a design that reflected the era through colour without designing a pastiche of Acid House - because Blackburn Parties weren’t the smiley face stereotype that emerged.

SEVENSTORE: How did the initial idea for Flashback come about?

Jamie: I was commissioned as lead artist by the British Textile Biennial to respond to the theme ‘The Politics of Cloth.’ I spent almost two years developing new work that was informed initially by the collections of The Harris Museum in Preston, and the Museum and Art Gallery in Blackburn. Both institutions exist as a consequence of the wealth that both towns accumulated during the industrial revolution, and both have collections that reflect the communities that gathered to work in mills and factories and function as archives for working class culture. This led to an exploration of other archives, and in particular the Mitchell and Kenyon film archive, where people are captured; and reveal so much of themselves and the time they are in - but don’t speak. All that’s missing is their voices. I realised that we had a continuous narrative of the people who inhabited our mills, warehouses and factories, but only to a point. It was the 30th anniversary of ‘Live the Dream’ in Blackburn and was therefore classed as heritage. Alex and I both think that it is important to capture these stories now and allow the participants to speak to kids and researchers in the future - in the same way that the Mitchel and Kenyon archive spoke to us

SEVENSTORE: What intentions did you have for covering the archive?

Alex: After a few interviews we reflected on how many different viewpoints there are and what this meant in people's lives. Up to 10,000 came to these parties so that created a hell of a lot of different experiences. We also knew it was almost impossible to fully fact check these interviews so we created a methodology which you can find on the site. We attempted to remove our own bias and collate a human story that was more about individual experiences and memory.

That meant no editing of the interviews, unless someone potentially put themselves at risk of a knock on the door from the police for a historic crime charge!

We were really working to highlight working class stories and put them on the map.

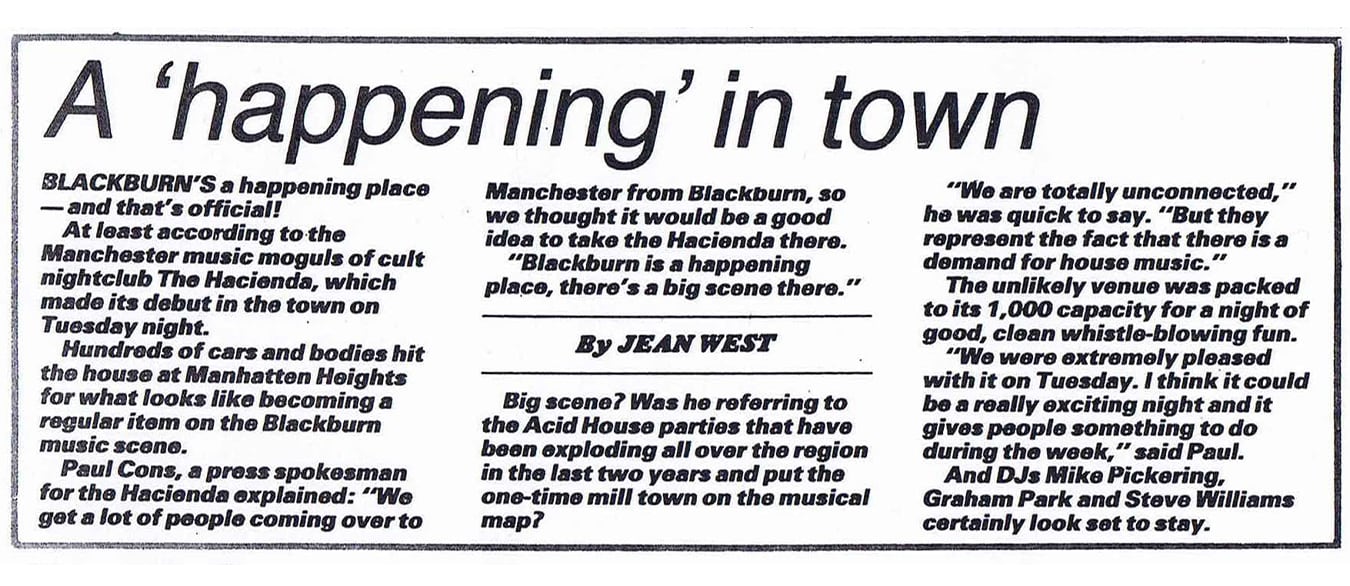

Jamie: The intention was to continue the story of working-class struggle and the impact that working class culture has had in manifesting youth culture. The mill teams of the North West were founders of the football league, and within a generation are responsible for forming new cultures and communities on and off the terraces. The football league gave us new rituals; communal singing, tribal behaviours and of course terrace fashion. We could see the beginnings of this culture in the Mitchel and Kenyon archive, where we also found a very early ‘cowboy film,’ that is now accepted as the world's first Western. The fact that a bunch of Mill workers from Blackburn invented a Hollywood genre was almost lost. We were determined to keep telling these extraordinary stories that are all linked to the mills and factories of the North, to attempt to preserve culturally important moments for the future. Blackburn had already been written out of the story, overshadowed by Manchester and the M25 parties.

SEVENSTORE: Why do you think it was important to pay homage to this certain time in culture?

Alex: Last year marked 30 years since the pinnacle of Blackburn’s Acid House parties. Some people consider 30 years to be the point where something becomes ‘heritage.’ Uncultured Creatives explores the idea of ‘future archives.’ Flashback was funded by Heritage Lottery Fund and shows their forward thinking about preserving heritage for the future and recording social, cultural and working-class cultures.

Jamie: There are two reasons; the first being that it is important that we do celebrate and make visible this period as culturally important. Acid House and, indeed, the terrace cultures that preceded it, is still not discussed with the same currency as so-called ‘high cultures.’ This reinforces a narrative that suggests that towns like Blackburn, and indeed much of the North, does not have worthy culture. This is an issue to this day, we think it’s important to challenge this narrative and reclaim notions of what culture actually is. The second reason is that Acid House was politically important. Although the interviews make it clear that for some participants it was hedonism or escapism rather than revolution or dissent that motivated them, this is, in itself, a political statement. Particularly in the context of the late 1980’s, high unemployment and Thatcher’s government destroying industrial communities across the North of Britain.

SEVENSTORE: There is a historical value to uncovering the accounts of people that were placed there at those times. Why was it so important to choose a variety of people and how did you go about picking who was included?

Alex: We set up drop-in recording sessions at the Prism Contemporary, an art Gallery Jamie and I co-direct in Blackburn. We recorded 17 people on the first session working with Joe Fossard, a sound engineer who used to set up the PA at the original parties. Joe was a massive part of the project, helping us carry out interviews and connecting us with unique voices.

Jamie’s research for The British Textile Biennial had already helped establish relationships with people from that time and it’s always been important for us to honour the integrity of these stories - the project wouldn’t have happened if it weren’t for people like Tommy Smith and Joe helping us connect with people from the era. We also wanted to record a full arc of perspectives so we actively sought out people like police, journalists, local residents, DJs and MP’s.

SEVENSTORE: Do you feel this underground movement was the result of post-industrial Blackburn? A way for a generation of disenfranchised youth to let go of external problems?

Alex: Definitely; unemployment, poverty and deprivation in Northern towns was contrasted with the 80’s boom seen in the big cities. Young people were being made to dress up in shirts and ties to go out to nightclubs - the nightlife and music culture in London didn’t make sense in a town like Blackburn. And I'm sure that was just one small reflection of what was felt across all aspects of life in these small towns. It was no wonder people kicked back.

Jamie: As Tommy Smith, one of the party organisers says in his interview - Blackburn was made for the movement. The landscape was a mix of empty mills and factories, alongside newly built and immediately abandoned warehouses and industrial estates that would never fulfil the role they were intended for as unemployment soared. In retrospect, they had nowhere to go, so they reclaimed these spaces as their own.

SEVENSTORE: Do you think it was in those times it was in the nature of the working-class to be rebellious?

Alex: I think it’s periodically but consistently been the nature of the working class to be rebellious throughout our history.

Jamie: I agree with Alex, the work we made for The British Textile Biennial revealed two hundred years of radical activities, people and cultures. From suffragettes to trades unions, from mill poets, pit painters and the football terraces. Much of what we now accept as mainstream culture, manifests originally on working class rebellion.

SEVENSTORE: Why do you think such parties were so popular?

Jamie: They were democratic. Like the punk movement before them, they rejected the ‘superstar’ hierarchy of rock music, but embraced new technology rather than elevating the cult of the individual. Shack was one of the first DJ’s at the parties and he talks about DJing before it became a desirable option. He says no one wanted to do it at first, so for most kids it was very much about participating, and of course dancing. I think the historical context is important, the interviews we recorded make links to Northern Soul and the Jamaican community in Preston. Both cultures have a history of all-night dancing and of sound systems.

Punk was also an important influence, you can see that in the flyers and the fanzines of the time, as was terrace culture. Lots of the kids going to parties had been involved in fighting at football, and some in right-wing politics. All of that dissipated when the parties started. The interviews mention unity, coming together, hope and a sense of community regardless of background, gender or race. It’s the collision of all these influences, people being tired of the violence, politics and poverty of the era plus this exciting new music and this equally exciting new drug. All of this contributed to the popularity of the parties.

And when you look at the photographs we have on the archive, you can see how exciting it must have been.

SEVENSTORE: Do you have a particularly favourite interview/story you have from the archive?

Alex: I know we both really loved Geordie - he’s such a straight talker and really enjoyable to listen to. One I think reflects on the various important impacts the parties had on the town is Shack’s interview. A DJ who covers the evolution of this totally new musical sound, what was happening in Blackburn that instigated this rebellious nightlife and how the scene impacted some of the football and racially motivated violence in the area - for the better. His interview really covers the social history aspects of this era which was a bit of a goal for the work.

SEVENSTORE: Do you feel with the acid house movement in Blackburn and The Hacienda in Manchester, the North West has formed a certain sense of youth culture?

Jamie: I think that the North West has multiple, complex and rich youth cultures that continue to emerge and challenge the mainstream culture, or that of London and other larger cities. There’s no doubt that Factory records, The Hacienda, Acid House and the terrace culture associated with our football clubs and fans continues to define that sense of identity. You can see this in the adidas Spezial range, and in the cross-over between music, art and street fashion. My own view is that working-class kids have always dressed up, organised themselves and have expressed their ideas and identity through clothes, art, activism and music. In doing so, they changed their world, and the world around them.

A new series of interviews, never seen before images and a map of Blackburn’s party sites goes live on from FRI 17 JULY.

Flashback is a project commissioned by The British Textile Biennial and funded by Heritage Lottery and Arts Council England.

Thanks to curators Alex Zawadzki and Jamie Holman